Early Church and Imagery: A brief Historical analysis

After a historical overview, we take a look at the concepts of ‘iconodulia’ and ‘iconoclasm’ in the Orthodox Church and how they relate to each other.

[This was part of an essay I wrote in a class on holy images and worship at the “Newmaninstitutet”. Changes have been made to it for this publication.]

One question that became controversial in the Church was the role of images. Are images licit as means to facilitate the presence of God or is the invisible God best represented through the written word? Are there some meaningful distinctions between icons and idols? What exactly is an image to begin with? Although these questions find primarily their historical context in the 8th and 9th centuries in the East, and in the 16th century with the Reformation in the West, the question of idolatry, worship and imagery is not new to those times.

Something that should be dealt with from the outset, is why, if early Christians did not have a reservation to images, we don’t see this reflected in the Bible? If scholars like Robin M. Jensen and Jaś Elsner are right, that early Christians were not hostile to imagery as such but objected to idols, then how is the absence of images supposed to be explained? At the outset we should take notice of a methodological problem with a question like this. ‘The Bible’ as a set of canonical texts was not fixed until many centuries after the birth of Christ. Some texts that were viewed as Scripture by some did not make it into the canon, yet others that were debated finally did. Dealing with the historical record, we can’t anachronistic presuppose a canon that was yet not fixed. We need to consider a broader set of ancient Christian literature.

But let us say something of a passage in the New Testament (there are plenty of examples of positive attitudes of images in the Old Testament) in which imagery actually does play a role. In Mark 12:13-17 we can read:

“13Then they sent to Him some of the Pharisees and the Herodians, to catch Him in His words. 14 When they had come, they said to Him, “Teacher, we know that You are true, and care about no one; for You do not regard the person of men, but teach the way of God in truth. Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not? 15 Shall we pay, or shall we not pay?” But He, knowing their hypocrisy, said to them, “Why do you test Me? Bring Me a denarius that I may see it.” 16 So they brought it. And He said to them, “Whose image and inscription is this?” They said to Him, “Caesar’s.” 17 And Jesus answered and said to them, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they marveled at Him.”

The relationship between Christianity and imperial images is not monolithic. At times, when it was expected by Christians to worship the emperor and his image, many refused. But as we enter the 4th century the patristic consensus seems to be that obeisance to the emperor’s image was tolerated, because it was not thought of as worship since the emperor did not claim divinity to himself. The distinction between worship and veneration was therefore to have been presupposed, even if it was not always expressed conceptually (Setton, 1941).

What stands out in the above pericope is that Christ does not seem to be troubled by the image or εἰκὼν of the emperor on the coin but rather makes a move similar to the one made by Basil the Great and later iconodules, that there is a relationship between the image and the one imaged. If one is to elaborate here a bit, Jesus also says that “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s”. This second clause may be referring to the creation of man in the image of God: ‘since you are in the image (ikon) of God, give yourselves to Him’.

Christ is asking the questioners to look at the coin and he himself does likewise. This might be seen by our culture as insignificant, but we would argue that to look at an image that essentially is idolatrous is not an uncontroversial move. Some would have found it objectionable. On the whole, this passage agrees with the some of the central assumptions about the relationship between the prototype and the image by the iconodules in the 8th century and at the same time counters the iconoclastic assumption that a real image must be of the same essence with the prototype. Although this passage says something about the role an image can play, it is not clear from the passage alone if we are to understand the image on the coin as a “presence” or as an “absence”. As Elsner points out about images, “... the problem of representation and especially the question of whether an image, as an imitation of its referent in a pictorial medium, is not the same as its referent and thereby expresses the absence of that referent even as it refers to it, or whether it is a site for the real presence of its prototype, embodied in the image.” (Elsner, 2012).

Jensen underlines the previous religious and ideological commitments to the question if iconoclasm:

“The assumption that ancient Christians unfailingly and universally condemned pictorial art because they believed it to be idolatrous has endures despite historians’ efforts over the past half century to qualify this belief. The notion that early Christians were aniconic (against all pictorial images, especially of the divine) and even iconophobic was fostered by influential Protestant Reformers like John Calvin, who, citing the biblical commandment against images (Exod 20:4-5; Deut 5:8), believed that scripture condemns religious iconography, particularly any that depicts the Divine Being… Much of the persistence of this error derives from centuries of misreadings of Christian apologetic texts that disparage depictions of polytheists’ gods, wrongly judged to be sweeping and effective critiques of all types of religious pictorial art.” (Jensen, 2022, page 1)

Jensen do argue for a development but not for an essential change in perception, from aniconism to an iconophile position. She gives multiple reasons, both of different points of views and as possibilities, for the absence of Christian art in the first two centuries, which includes the changing socio-economic situation (Jensen, 2004). This is a theory that is especially developed by Paul Corby Finney. He writes: “The reason for the nonappearance of Christian art before 200 have nothing to do with principled aversion to art, with otherworldliness or with antimaterialism. The truth is simple and mundane: Christians lacked land and capital. Art required both.” (Finney, 1997). Likewise does Elsner argue against the previous consensus. The new emerging consensus is rather the opposite: “The modern consensus is that the attacks on idols by the early fathers and Christian apologists are primarily directed against pagan polytheist practices in the Greco Roman environment rather than against the Christian cultivation of religious images.” (Elsner, 2012).

Having said all that, there is still something important to be said for a reluctance toward depicting the divine. Charles Freeman summarizes it like this: “There is nothing from before AD 200 which can be recognised as distinctively Christian art. This is partly because Christian communities were small and poor, but it is possible that traditional Jewish conventions about portraying images may have inhibited them.” (Freeman, 2011). In a way, the later iconodulic argument that the incarnation plays a central role in the permissibility of the depiction of the God presupposes the correctness of the argument that a non-incarnate God should not, or rather could not, be depicted. One should notice here however that we do actually have literary evidence of Christian art, that is, art with distinctively Christian motifs, or alternatively, common symbols used in a Christian context, as early as the 2nd century. This, within different gnostic groups, and possible also in the early 3rd century with the emperor Alexander Severus (Chadwick, 1993), although this is uncertain. But even within proto-orthodox Christianity we have literary attestation of Christian images, on cups and signet rings, that may very well be in existens before the magic line of 200 AD. This, because many of the writers that talk about them, lived around that time and it is not always clear as to how far back in time the were aware of such practises. If we also assume that these rings were kissed, we have something that starts to look like later Christian veneration of icons. Not in a liturgical sense, but non the less in practice. In other words, the common and almost sweeping statement that is echoed about the absence of art in the first two centuries, like the statement above by Freeman, must be qualified to be referring to the archeological sphere. Finney leaves the door open for the possibility of the existence of Christian art before the 3rd century (Finney, 1997) that we may one day find, but this seems to be an unnecessary statement since we already have indications that Christian art existed before then, we have just not found it. If we consider literary evidence, we are told that images of Christ and saints existed already int h 2nd century. Documents like Acts of John and a statement by Irenaeus makes it clear that images with distinctively Christian motifs in the 2nd century existed. In a sense, the discussion about the absence of Christian art before the 3rd century and the explanation for this perceived fact becomes a question of historical medium. There are many examples in history when a certain historical fact or practice is not attested in all possible mediums. In the ancient Greek religion for example, there is an absence in the visual arts of important acts in the religious life: “… the actual killing of the animal in the course of the sacrifice is hardly ever shown in ancient images, and the consumption of the meat is completely absent… Other practices of Greek religion that are known from textual sources are not shown in Greek imagery.” (Gaifman, 2015). Likewise, in ancient Christian literature, evidence of Christian art does exist, whether this contains specifically Christian motifs or borrowed ‘secular’ images that are appropriated to a Christian context, as is the case with the signal rings mentioned by Clement of Alexandria. Clement is also allowing for the depiction of the apostles; he is more drawing the line against idols and symbols that condones violence or unethical behavior (Jensen, 2022). There are some examples of Christian rings that includes things like scenes from the Bible, like one of late 3rd or early 4th century, depicting Jonah.

Perhaps the difficulty in the evaluation of early Christian attitudes arises out of our methodological approach. Should one give more weight to a handful of early Church writers’ views, that primary had idols as their targets anyway, over the ‘reality on the ground’? That is, should unofficial religious practices be judged through the opinions of individuals that are conceived of as having a more official institutional role? One can for religious commitments make this move, but should the historian be bound by them? Surly, if the question is how early Christians viewed art, we should not exclude the ordinary men and women from this investigation. If we are, for example, going to say that the council of Elvira is evidence to the aniconic position, we must also add that the opposite is true, that in the early 4th century, Christian art and its veneration was so widespread that some bishops wanted to regulate it. No canon is created in a historical vacuum, and although the meaning of the relevant canon is ambiguous (Jensen, 2004), if we take it to mean that it prohibits the depiction of saints on the church walls because they run the risk of being adored, we can assume that this was something that had already occurred and hence this canon is an indirect witness the reality on the ground. We should not reconstruct history merely through the lens of those that wrote it, especially if we have good reasons to think that the truth of the matter is more complex. But even with these early Church writers, to the extent that they do comment on Christian art, like Tertullian or Clement of Alexandria, we notice that they are open to at least some art (Chadwick, 1993) and as we will see, the divide between official and unofficial religion has some problems.

If the argument is that the early Christians were proto-iconoclasts, that they for principled reasons avoided making images, then it becomes difficult to explain the sudden emergence of images in our archeological record in the 3rd century A.D. We are forced to say that Christians that grew up hostile to art, as soon as they gained land and capital, changed their mind and adopted a contrary point of view. Many scholars believed that the earliest Israelites were polytheists, but Rainer Albertz points out that this in itself don’t answer the question why they then became monotheists: “No, there must have been a potential for difference within Yahweh religion which distinguished it from the usual polytheistic religions, a potential to which opposition groups which saw the exclusive worship of Yahweh as the only possibility of overcoming crises could appeal. To this degree the approach of earlier scholars, who started from an inherent tendency to monolatry within Yahweh religion from the start, still has a lot to be said for it.” (Albertz, 1994). Likewise, the stark aniconism-model lacks explanatory power to explain to appearance of images. There must at least have been something from the outset the distinguished Christianity from other religions.

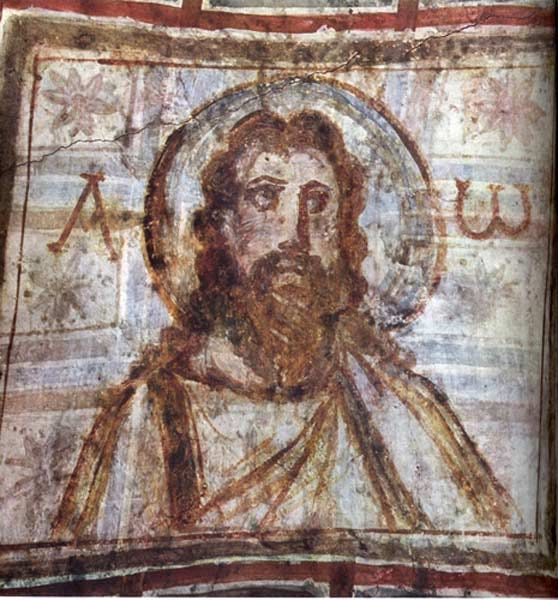

However, we don’t really see a clear-cut separation between official religion and unofficial on this matter, between dogma and impious customs, or between orthodoxy and heresy. There are voices and examples from both sides. There are gnostic groups that do affirm Christian art but also some that stand skeptical to it, likewise, examples of positive attitudes to Christian art can be seen, even in the very writers that are usually counted as clear iconophobs. One of the strongest arguments for this is perhaps the catacombs. The catacomb of Callixtus, which contain one of the earliest types of evidence of Christian art, was run under the supervision of the local Roman Church. It was their official burial place, and many pre-Constantinian Roman bishops were buried there, and it can therefore be plausible assumed that there was an awareness of what was going on in there. In fact, Callixtus, the deacon-supervisor, later became the bishop-pope of the city. This is contemporary to Tertullian, Origen and Clement of Alexandria.

In what is to follow, we will argue that actually both tendencies of iconophilia and iconoclasm are passed down to what became the Orthodox tradition. Although we usually think of orthodoxy as iconodulic, we do forget the ways in which it incorporated and passed on both tendencies. This is a fact that is expressed more broadly in human existence, not out of theological consideration (even if it is that too) for is it really possible to be fully iconoclastic? And if it is, what is the cost to the different dimensions of our existence? Do we need to destroy all secular images to? After all, the second commandment does not make a distinction between private and public property, or between religious and secular art, if we are to interpret it to be referring to the categorical denial of images and their worship. Likewise, can someone live as there is no such thing as a problematic depiction? There is a sense in which we can say that the battle has never been between iconoclasm and iconodulia but where exactly we should put some boundaries. At which point are some theological and historical lines crossed? The 7th Ecumenical Council did not only affirm the permissibility of depicting Christ and the saints, but it also laid boundaries as to when it turns into idolatry, and it understood that there had been some kind of development from the earliest days to their own. What they essentially objected to was that this constituted a change in dogma. Deacon Epiphanios, in the sixth session of that council, read out and said, among other things, that: “We accept whatever at various times our celebrated fathers decided to ‘built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets’…” (Price, 2018). The idea that the council fathers are not aware of any kind of “building on” is probably, at best, a misunderstanding of the argument by the same fathers that they are not adding or subtracting anything of the faith. Allan Doig summarizes the orthodox view like this: “The orthodox position is very careful to insist that there is nothing novel either in the doctrine or in the images themselves – all is compatible with the received tradition, though elaborated.” (Doig, 2008).

Early Christians, on a general front, were not against art as such but objected to idolatry. But, there is something that is often overlooked and will perhaps sound strange due to how we are usually drawing attention to these things. It is that the Orthodox tradition does contains the totality of the Christian tradition, not only the theology of the icon as a positive affirmation of the incarnation of the second Person of the Trinity and the essential goodness of matter, but also a sober sense of the limitations and boundaries, not only of art and depictions, but even of concepts as such. There is an ever presence sense in orthodoxy of the limitations of our categories and the distinction between the created and the uncreated. Hence, in a very real sense, that themes of ‘iconodulia’ and ‘iconoclasm’ always existed in orthodoxy. The 20th century Romanian theologian Dumitru Stăniloae writes: “The fathers speak of the higher and intellective part of the soul, nous or mind, in a way that suggests that the mind has been freed from all representations and images of the things of the world, it knows God in a direct intuitive manner” (Stăniloae, 2000). This more contemplative prayer has its goal to move beyond any concept, written of painted, printed or mental, into a clear and immediate knowledge, that is, relationship, with God. Against this background, the theologians of the 20th century don’t sound that very different from those writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries that argues against idols by way of referring to the incorporeality of God. Yet, no one can argue that Stăniloae was against icons.

Four other brief examples of ‘iconoclasm’ is 1) the avoidance of making religious images in three dimensions and 2) the reluctance of making portraits of God the Father. We see in here the ‘iconoclasm of the iconodulic position’. Just as orthodoxy preaches God the Son incarnate through depictions, it preached that God the Father is not incarnate by not depicting him. 3) One could also mention the Quinisext Council, that forbids certain kinds of images and lastly, 4) as we have already hinted at, the Orthodox Church urges the faithful to not use fantasy as a means in prayer. Mental images are hence discouraged.

On a broader point, this fact of drawing the line somewhere as to what is acceptable and what is not, is something one is forced to do, consciously or not, as we explained above. In a concluding manner then, we might say that the word ‘iconoclasm’ is not really capturing the fullness of the matter at hand. A better word might be idoloclasm: the smashing and argument against idols. Orthodoxy is not only iconodulic but also idoloclastic for some of the reasons numbered above. And to be fair, though the iconoclast ultimately destroyed icons that have been loved for centuries, in their own minds, they were destroying idols.

The very real and tangible presence of God in history opened up this question and allowed Christians the freedom to give God a face, just as his many revelations allowed the early Israelites to give God a name. It is in virtue of this fact, that God can be depicted and named, that an inquiry into keeping these mental and not mental representations within orthodoxy begins. Iconoclasm is intertwined with iconodulia. God gives his name, but it is so holy, so the people are reluctant to even say it out loud. God gives us a face, but some started to feel in the 8th century that this face should remain unrepresented by human hands. In the end, the argument from the incarnation became too strong to resist, that a resistance to any kind of representation would undermine the oikonomia of God. And as we have seen, some of the core arguments against icons are undermined by the very words and deeds of Christ. It is not until the Reformation that the question is resurrected at the hands of the french and german theologians. But we should neither be afraid to call upon the name of the Lord (Rom 10:13) nor to look at the Icon of the invisible Father (Kol 1:15). The question of depicting Christ became a question of dogma for it was intimately linked to the incarnation and hence to Christology. The icons in the Church are, in other words, not a question of preference, but a statement of faith.

Bibliography

Albertz, R., 1994. A History of Israelite Religion in the Old Testament Period From the Beginnings to the End of the Exile. u.o.:SCM Press Ltd, p. 62.

Chadwick, H., 1993. The Early Church. Revised edition red. u.o.:Penguin, p. 277. Doig, A., 2008. Liturgy and Architecture: From the Early Church to the Middle Ages. u.o.:Routledge, p. 82.

Elsner, J., 2012. Iconoclasm as Discourse: From Antiquity to Byzantium. The Art Bullean, 3 September, pp. 368-394.

Finney, P. C., 1997. The Invisible God: The Earliest Christians on Art. u.o.:Oxford University Press, p. 108.

Freeman, C., 2011. A New History of Early Christianity. Reprint edition red. u.o.:Yale University Press, p. 169.

Gaifman, M., 2015. Visual Evidence. i: E. Eidinow & J. Kindt, red. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion. u.o.:Oxford University Press, p. 53.

Jensen, R. M., 2004. Face to Face: Portraits of the Divine in Early Christianity. u.o.:Fortress Press, pp. 4-9, 16, 20.

Jensen, R. M., 2022. From Idols to Icons: The Emergence of Christian Devotional Images in Late Anaquity. 1st edi0on red. u.o.:University of California Press, p. 1, 76-77.

Price, R., 2018. The Acts of the Second Council of Nicaea (787). u.o.:Liverpool University Press, pp. 522-523

Setton, K. M., 1941. Chrisaan Aitudes Towards the Emperor in the Fourth Century. New York: Columbia Univercity Press, pp. 196-211

Stăniloae, D., 2000. The Experience of God, Vol. 2: The World: Creation and Deification. u.o.:Holy Cross Orthodox Press, p. 74.